Ever paused with your hand over the recycling bin, wondering whether to drop in that cheese-splattered pizza box? You could be a wishcycler – keen to recycle more stuff and do your bit for the planet, but confused about the best way to go about it.

Wishcycling, or aspirational recycling, describes the well-intentioned, but often unfounded belief, that something is recyclable, even though it’s not. We’ve followed five items that cause recycling confusion on their journey through a recycling plant to help you think before you throw.

‘It is not always simple’

From a metal gantry high above the factory floor I watch bits of cardboard, shards of billowing plastic and other ephemera hurtle down a conveyor belt. The whirr and clank of machinery fills the air, and there’s a slight whiff of garbage as a truck disgorges a steady stream of recycling on the floor.

A forklift truck piles everything on the belt, ready for sorting. Covering an area of 20,000 square metres – nearly four football fields – this site in central London handles 120,000 tonnes of recycling a year, or roughly 25 tonnes per hour.

“What we’d like to convey to people is that recycling does work – there are a hundred facilities like this one across the UK,” says Tim Duret, director of sustainability technology at Veolia UK, which runs this plant in Southwark. “The objective is to sort the mixed waste into different fractions – the glass, the plastics, the metals and the fibre [paper and cardboard]. And we understand that it is not always simple to know what can and what can’t be recycled.”

You can say that again. Turn over a food packet and you’ll find a mindboggling array of recycling symbols. And while the packaging might say something is recyclable, that doesn’t mean your council will accept it. One council’s recycling is another council’s general waste, so it’s important to always check your local rules.

Here in London, hand pickers wearing gloves and masks are the first line of defence against the wishcyclers. Their hands shoot out with lightning speed to snatch things from the conveyor belt that shouldn’t be there, from plastic bags and bits of polythene, to what looks like a plastic hose.

Plastic causes particular confusion, with the likes of carrier bags, frozen food bags, bread food bags, crisp packets and pet food pouches often ending up in the recycling bin by mistake. “That is by far and away the largest amount of stuff that isn’t targeted by the local authority, so comes into your wishcycling bracket,” says Helen Bird, recycling expert at the waste reduction charity, Wrap.

She says some supermarkets are starting to collect crisp packets, plastic bags and other food wrapping in an effort to build new markets for products made from other types of plastics, from refuse sacks to toilet brushes.

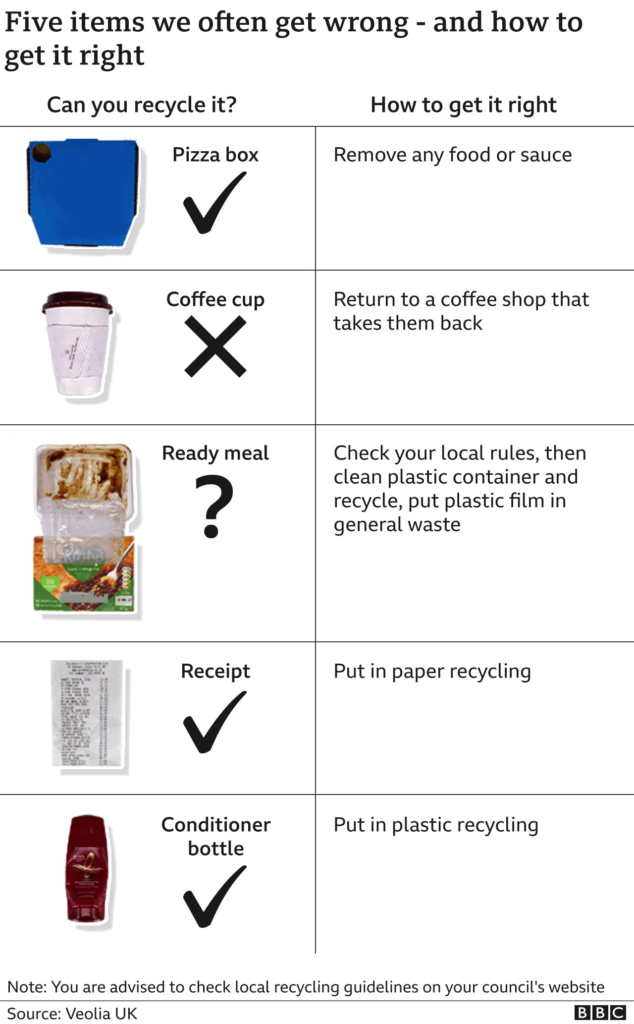

I’m not sure if my plastic conditioner bottle can be recycled and, as it turns out, I’m not alone. According to Wrap, more than half of households put items in general waste that could be recycled, including shampoo and conditioner bottles, cleaning and bleach bottles, foil and aerosols. “If it’s plastic and bottle-shaped it can go in [the recycling],” says Helen.

My ready meal container presents another dilemma. Tim says the plastic tub is accepted here, but that’s not the case everywhere. The plastic film can’t be recycled, though. It must be peeled off and put in with the general rubbish. As for any lingering lentils and mash – “3D” food, as he puts it, should be scraped off and emptied out.

My coffee cup is a firm reject. Though made from a type of fibre – cellulose – the cup has a thin plastic lining, which rules it out. And the plastic lid can’t be recycled either; instead the whole caboodle should be taken to coffee shops or other outlets, such as railway stations, which run take-back schemes. If kept separated from other materials, coffee cups can be recycled.

Thankfully, my pizza box, while greasy, isn’t so messy it fails the test. Tim drops it on the conveyor belt, where I watch it leap down the line to join other cardboard boxes. My shopping receipt can go in too. I was worried it was made of the wrong kind of paper – some are printed on shiny paper that can’t be recycled in many places. It’s another item that causes confusion. I’m told mine is fine.

Relieved some of my things have passed muster, I’m shown some of the more extreme items rejected by the hand pickers. There are frying pans, bits of a microwave, parts of a television. And textiles such as jeans and tights, which can get tangled up in the machinery causing the whole production line to grind to a halt.

When we stare down at the optical sorters – a series of spinning discs that sort things by size and shape – we notice a long pink ribbon has wrapped itself around part of the sorting apparatus like a snake. “There are people who will put any old rubbish in the recycling,” Helen says.

“Things like nappies, sanitary products, dog poo, dead animals, syringes. The belt will be stopped – physically somebody has to go through that stuff and pull it out. Fortunately, they are really in the minority.”

As we walk along the gantry, different streams of glass, plastics, metals and paper are emerging and chugging off in different directions as the machines sort stuff by size, shape, colour and structure, using lights and lasers, magnets and artificial intelligence.

New bicycles

“At the end we still rely on people to manually touch the waste and remove what’s not meant to be there on the belt,” says Tim. “Then we are sure that at the end of the process we’ve got sorted material: clean, 99% pure, which can then go to another facility.”

We go down to the factory floor, where all the sorted material is waiting to be collected. Bales of squashed cardboard and paper are stacked up higher than my head, ready to be taken to the paper mill. The plastics and glass will go off to be separated out and processed, while the aluminium and other metals can be taken to smelters to be re-melted and turned into new things, such as bicycles.

Recycling can reduce carbon emissions, because producing new products from recycled objects generally saves energy. Making aluminium cans from recycled scraps of the metal, for instance, is far more energy efficient than making the same from scratch.

And figures show we are getting better at recycling. According to Wrap’s latest survey, we’re now very much a nation of recyclers with nine out of 10 people recycling, saving 18 million tonnes of CO2 every year, the same as taking 12 million cars off the road.

“Ultimately, we’re all just trying to do our best – we all really want to recycle as much as we can,” Helen says of the wishcyclers. “It’s down to the companies that produce the packaging to start with to make it simple in terms of design and for the local authorities to be able to collect the stuff.”

But there are limits to what recycling can achieve, when it comes to reducing emissions. Tim says while there has been a “huge increase” in recycling rates in recent years, we need to do more, which relies on government investment.

“Technically we know how to do it, but we need more facilities in the UK, which will create jobs and help the economic recovery,” he says. And there are those who argue we need to re-think our whole approach to waste – after all, isn’t it better to buy less in the first place?