A growing number of brands are switching to recycled fibers but experts worry people may believe their purchases are impact-free – when that’s far from true

Woven into your clothes is a material that takes on many disguises. It may have the texture of wool, the lightness of linen or the sleekness of silk. It’s in two-thirds of our clothing – and yet most of us don’t even know that it’s there. It’s plastic, and it’s a big problem.

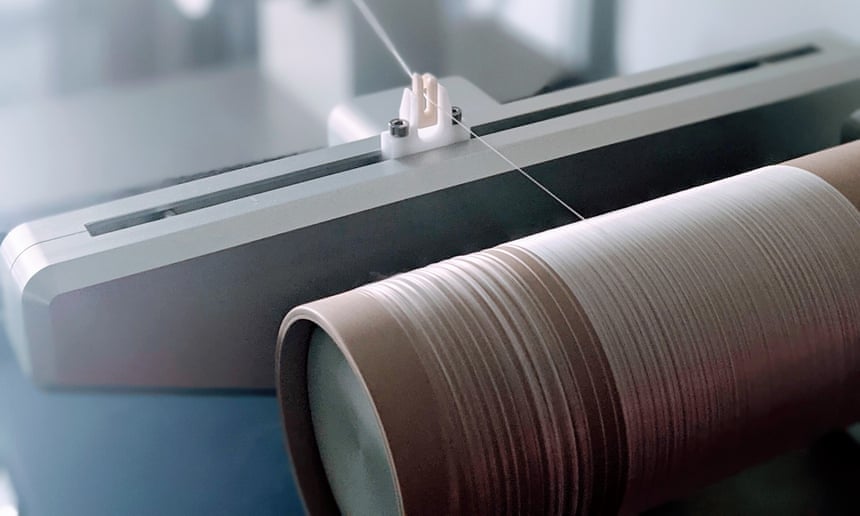

Today, about 69% of clothes are made up of synthetic fibres, including elastane, nylon and acrylic. Polyester is the most common, making up 52% of all fiber production. Plastic’s unique durability and versatility have made it indispensable to the fashion industry.

“It’s in the waistband of your jeans, your shoes, in practically everything you wear, because plastic is this miracle material,” said George Harding-Rolls, campaigns adviser at the Changing Markets Foundation, an organization that investigates corporate practices.

But there’s a climate cost: the raw material for these fibers is fossil fuels. Textile production consumes 1.35% of global oil production, more oil than Spain uses in a year, and significantly contributes to the fashion industry’s huge climate footprint. Synthetics also continue to have an impact long after production, shedding plastic microfibers into the environment when clothes are washed.

In response, a growing number of brands are switching to recycled versions of synthetic fibers like polyester, often advertising these clothes as the “more sustainable” or “conscious” choice.

This seems like an environmental win. But as brands weave more of these recycled yarns into their garments, some experts question whether they are just patching over fashion’s environmental harms. “We’ve been led to believe that recycled and sustainable are synonymous, when they are anything but,” said Maxine Bédat, executive director of the New Standard Institute, a non-profit pushing for a sustainable fashion industry.

The common recycled substitute for virgin synthetics are polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles, the most common type of plastic bottles, which are produced in the billions each year. A survey of nearly 50 fashion brands by the Changing Markets Foundation revealed that 85% of them aimed to source recycled polyester from plastic bottles. Estimates show that recycled polyester could reduce emissions by up to 32% compared to virgin polyester.

The demand for recycled synthetics from industries including fashion is expected to accelerate. Nike uses “some recycled material” in 60% of its products, said Seana Hannah, Nike’s vice-president of sustainable innovation. Recycled polyester is a primary focus: “Nike is the highest industry user of recycled poly and we divert more than 1bn plastic bottles on average a year from landfills,” Hannah said.

Many big brands are setting targets. H&M, Madewell, J Crew and Gap Inc are among more than 70 brands that have committed to increase the share of recycled polyester to 45% by 2025 as part of a recycled polyester challenge set by the Textile Exchange, a non-profit working to increase uptake of lower-impact fibers across the textile industry.

Synthetics make up the second-largest share of fibers after cotton for Gap Inc, said Alice Hartley, director of product sustainability and circularity at the company. All four of its brands – Banana Republic, Old Navy, Athleta and Gap – have committed to the 2025 challenge, with Old Navy opting to increase its recycled polyester to 60%.

The company says that recycled synthetics are not a magic bullet. “We really try to stay away from the term ‘sustainable garment’, because that implies that we’ve reached the destination. We really haven’t, it’s a continuous journey,” Hartley said.

Yet this nuanced message may not be filtering through to consumers, especially as many other brands do describe recycled fabrics as sustainable. Experts worry that people may believe their purchases are impact-free – when that’s far from true.

“If you are recycling synthetics, that doesn’t get rid of the microplastics problem,” said Harding-Rolls. Fibers continue shedding from recycled plastic yarns just as much as from virgin yarns, he said.

PET bottles are also part of a well-established, closed-loop recycling system, where they can be efficiently recycled at least 10 times. The apparel industry is “taking from this closed-loop, and moving it into this linear system” because most of those clothes won’t be recycled, said Bédat. Converting plastic from bottles into clothes may actually accelerate its path to the landfill, especially for low-quality, fast-fashion garments which are often discarded after only a few uses.

“One of the hallmarks of greenwashing is taking one piece of the puzzle and extrapolating broad benefits from that,” said Ashley Gill, senior director of standards and stakeholder engagement Textile Exchange. “Sustainability in the apparel industry is a really complex issue.”

There are moves to use recycled textiles as feedstock for new clothes – less than 1% of clothes are currently recycled into new fibers – especially as projections from some markets suggest that cross-industry demand for recycled bottles will soon outstrip supply. But most clothes are made from a medley of fibers, and commercial-scale technology doesn’t yet exist to disentangle these. “A whole supply chain needs to be built up to really get to the commercial volumes that we need, to see more recycled fiber-to-fiber textiles,” Hartley said.

Hyping the lower emissions impact of recycled yarns, said Bédat, distracts from fashion’s larger emissions source: textile mills, which process fibers into yarn to make fabric as well as dyeing and finishing, an energy-guzzling process that accounts for about 76% of a garment’s lifecycle emissions. “Brands are focusing on what magical material they can create, rather than doing the less sexy work of improving energy efficiency in textile mills,” said Bédat. “I don’t want to pooh-pooh progress, but we really do have to start prioritizing where we’re going to be able to move the needle the most.”

Some innovators think the solution lies in finding viable alternatives to fossil fuel-derived synthetics that have the same performance traits. Materials science company Kintra Fibers has developed bio-based fibers made from corn and wheat designed to compost fully in nature. “That addresses the microfiber issue, and provides another pathway for textile circularity as well,” said Alissa Baier-Lentz, the company’s co-founder.

The fiber can also be returned to its base components through chemical recycling and used as a feedstock for circular yarn production, Baier-Lentz said. “It’s just on us to get the [recycling] system in place, and work with industry partners to make it happen,” she said. In 2020 Kintra partnered with clothing brand Pangaia to scale up production of the compostable yarn; the company will launch the first clothes made with Kintra fibers in 2022.

But no one innovation is going to solve the fashion industry’s complex plastics problem. Some think the real answer is moving the industry away from a model of excessive production and consumption. Brands churn out dozens of clothing collections a year and, in 2014, people bought 60% more clothing than in 2000 but kept it for half as long. Textile Exchange will focus some of its future industry challenges on “slowing down the growth rate” of clothing production, said Gill.

Legislation will be needed to drive real, systemic change, said Harding-Rolls: “[The apparel industry] is one of the most lightly regulated industries in the world. What we need now are mandatory measures. We see it working in the plastics space, and it’s time for the fashion sector to follow.”

There’s a role for us, too, said Bédat, and that involves people seeing themselves as citizens who can make ethical and political choices. “We’ve been trained to see ourselves primarily as consumers … that the way we solve these problems is by buying, which is the antithesis to the real solution.”