For years, clubs in England have regularly chosen to fly to Premier League matches.

It is generally the quickest and most convenient option and gives players and staff maximum time to prepare for games.

But as world leaders meet at COP26 in an attempt to avoid the catastrophic effects of climate change, is it time for that practice to stop?

Manchester United caused controversy when they flew to Leicester in October, a journey of roughly 100 miles with an estimated flying time of around 10 minutes.

The Red Devils were travelling the day before their game and said they would not normally fly but cited “circumstances” – there were reports of congestion on the M6 motorway at the time.

Forest Green Rovers owner Dale Vince, whose League Two outfit are regarded as the greenest in the world, told the BBC the Premier League side’s decision to fly to Leicester was “horrific”.

But the Old Trafford club are far from alone in travelling this way.

An Instagram post by Kalvin Phillips last month showed Leeds United taking a plane to Norwich City, a journey with an estimated flying time of 17 minutes. That match had been designated by the home club as a game to “champion sustainability practices”, with the Canaries encouraging supporters “to make small changes to their matchday ritual in a bid to become more sustainable”.

BBC Sport has been told the majority of clubs do travel by air to games at Carrow Road. Arsenal often use this method for journeys to East Anglia, despite being heavily criticised in 2015 for making that journey by plane.

A month earlier, Tottenham had faced criticism from Greenpeace after taking a 20-minute flight to Bournemouth.

In contrast, in 2019 Ajax opted to take the train from the Netherlands to France for a Champions League game against Lille, with the club’s chief executive Edwin van der Sar explaining that “we live in a climate-conscious time and we want to set a good example as a club”.

“From my perspective it’s about having a joined up football club,” said Vince. “At Forest Green we prioritise the environment and football equally so it would be impossible for the decision Manchester United made to happen at our club.

“At other clubs you have environment programmes that are bolt-on programmes and so the football side simply say it’s more convenient to fly, so that conversation doesn’t happen. It means the environment isn’t properly embedded in those clubs.

“Manchester United talk a very good game about the environment and they have done some stuff but it’s not good enough to say one thing and do another.”

Why are such short domestic flights a problem?

Flights produce greenhouse gases – mainly carbon dioxide (CO2) – from burning fuel. These contribute to global warming.

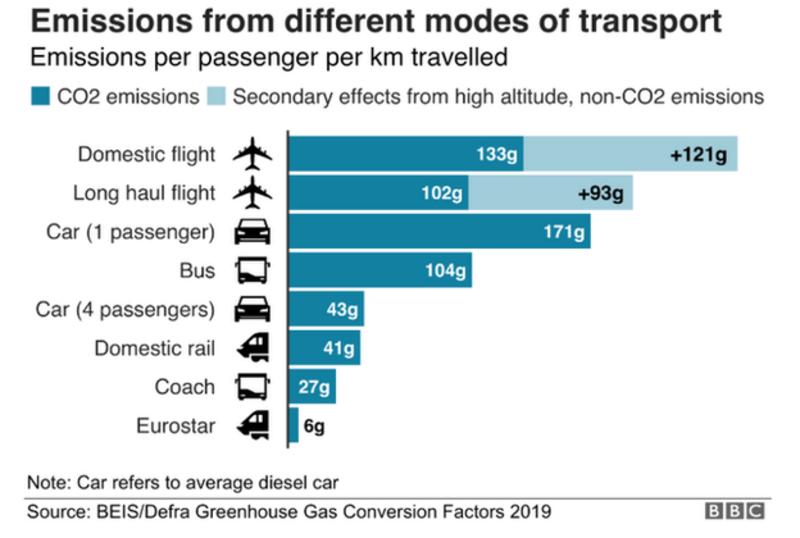

Emissions per kilometre travelled are known to be significantly worse than any other form of transport, with short-haul flights the worst emitters, according to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

In April lawmakers in France voted in favour of a bill to ban the shortest domestic flights. If approved at a second vote, this would mean removing routes that can be undertaken by train in two-and-a-half hours or less. Spain is considering a similar move.

And last month the Campaign for Better Transport called for the UK government to ban domestic flights if the journey could be done by train in less than five hours.

The biggest distance between Premier League clubs this season is the 348 miles from Newcastle to Brighton.

On a standard Friday (the day before the teams usually play), 12 of 14 trains departing Newcastle before 16:00 GMT take five hours or less to get to Brighton.

The majority of journey times for away games would be significantly less than that. In the case of Manchester United, the coach journey to Leicester from Old Trafford would generally take around two-and-a-half hours, with the train journey between the cities lasting a similar amount of time.

Julian Allwood, professor of engineering and the environment at Cambridge University, told BBC Sport that cutting avoidable flights such as the ones taken by Premier League clubs is an “obvious starting point” in the bigger challenge of reducing fossil-fuel dependent flying.

“We’ve had a period of two generations in which flights have been cheap and widely available, and that’s changed our expectations of how far and how fast we can travel,” said Prof Allwood. “But if we don’t act on climate change, in one generation’s time we’re going to be seeing mass starvation in the countries of the equator, and sport won’t be much on our minds.

“None of us wants to be part of bringing that about. Accepting slightly slower travel and reducing distances to avoid massive suffering looks like a great substitution to me.

“The government has rightly committed us to zero emissions by 2050, with a 78% reduction from 1990 levels by 2035. This will have very little impact on most of the things we enjoy – including playing sport.

“However, in the next 28 years we must reduce our use of fossil-aeroplanes in line with the government’s commitments. Eventually this will affect all international competitions, but in the short term reducing the use of flights where there are road or rail alternatives is the obvious starting point.”

So why do clubs fly to games?

Chartering a plane can be around five times as expensive as hiring a train carriage for exclusive use, and many times more expensive again than travelling by coach.

In many instances these journeys are made by road or rail – Manchester United generally travel to London by train, for example.

But convenience is a significant factor, as is the pursuit of the best sporting conditions for elite players.

A short plane journey is regarded as better for a footballer’s physical condition than a longer coach journey. Also, late kick-offs can mean the train is not a viable option, while the prospect of lengthy journeys may result in staying overnight after a match, limiting training and recovery time before the next game.

Leeds and England striker Patrick Bamford is involved with a sustainable sportswear company, is using his platform to raise awareness of environmental issues and is working with Leeds to make changes at the club, such as the introduction of more electric car charging points at the training ground and behavioural change among commercial partners.

He admits to feeling conflicted about flying to domestic games – such as his club’s trip to Norwich in October.

“It’s a hard one because first and foremost I’m a footballer,” he told BBC Sport. “Ideally the things we do have to be good for the planet as well as being good for what we’re doing. I do feel bad but I know it wouldn’t make sense for us to travel on the day of the game, for instance.

“There aren’t going to be many clubs who put themselves at a competitive disadvantage. I know at Leeds we try to fly as little as possible. We always get the train to London. We only fly if it’s the last option – if there are no trains to get us back or if it’s a really long way back, like Southampton.”

Matt Konopinski is director of physio and performance at Rehab 4 Performance and a former head of physiotherapy at Liverpool and Rangers. He says he has known instances where teams have taken a 30-minute flight to shave 90 minutes off a coach journey.

So how much of a difference does that make – if any – to players?

“There are benefits and drawbacks from a medical perspective of going on a plane,” said Konopinski.

“Top teams will prioritise speed over other factors but flying is not always a good thing.

“Yes players will be in a better state if they arrive in the shortest period of time. But we’re talking about one stage of preparation. You also have to factor in when people are eating, training and sleeping.

“With flying, one of the things we struggle with – anecdotally – is hamstring issues. I know there is a widely held feeling among physios that this could be one small element of the picture. The other negative can be when a player is already carrying swelling on the knee – that can be exacerbated. That can happen on short flights as well as longer ones.”

Coaches may be perceived as less luxurious, says Konopinski, but there are also positives as well as negatives to that form of travel.

“On a coach it is door to door, so no need for additional transfers,” he added. “You can also have your own chef on board, which can be a real benefit.

“But longer journeys can contribute to lower back issues as it’s harder to get up and walk around.”

So if he were at an elite club now, knowing what we do about the environmental impact of flying, would he be happy if his team chose to stop flying to domestic games?

“I would want to look at the medical evidence and there probably isn’t any firm evidence either way,” he said.

“Can’t you have a certain distance where a flight isn’t acceptable? Because often there isn’t a huge difference in time door to door and the environmental factor is a big one.”

‘Football has to sort its act out’

Last week the Premier League signed up to the United Nations Sports for Climate Action Framework, an agreement which asks organisations and clubs to commit to limiting the impacts of climate change.

The Premier League has pledged to reduce 50% of its own emissions by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2040, in line with the 1.5ºC global warming limit put in place by world leaders as part of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

In a statement, the Premier League said: “The league will also continue to work alongside clubs to look at ways to reduce environmental impact and will encourage fans and their communities to support this action, inspiring long-lasting behavioural change.”

So could it move to ban clubs from flying to Premier League games?

That does not appear a viable option, since clubs are responsible for their own travel arrangements and the league has no jurisdiction over them.

But it has issued travel advice previously. When top-flight football returned in June 2020 after a 100-day suspension because of the coronavirus pandemic, the Premier League reportedly encouraged clubs to fly to matches to help with social distancing amid health concerns, with some apparently chartering multiple planes.

On Tuesday, the UK’s chief scientific officer Sir Patrick Vallance told the BBC climate change posed a bigger challenge than the pandemic and added that behavioural change was needed.

Some of this change has begun within football. Four top-flight clubs (Arsenal, Liverpool, Tottenham and Southampton) are signatories to the United Nations Sports for Climate Action Framework, though none have signed up to the next level of this agreement, which requires organisations to cut carbon emissions in half by 2030, be net zero by 2040 and report annually and publicly on progress towards these goals.

Tottenham Hotspur and Chelsea recently travelled to their match on coaches run by bio-fuel, part of an attempt – involving Sky Sports – to host a game with net zero emissions.

“Our experience tells us football is the most incredible platform,” said Forest Green’s Vince.

“Over the past 12 months our media reach has been huge, with five billion impressions and fan clubs in 20 countries across the world because of what we stand for.

“There is a real appetite out there among sport fans and environmentalists for this kind of club to spring up and stand for something.

“Football has to get on and sort its act out and it has a massive ability to influence people.

“Given the sums of money available are the Premier League clubs doing enough? No. If we can afford to do what we are doing then so can those clubs. And they have the biggest platform and ability to influence people.”